Russian Fish Find Way Onto American Tables Despite Import Ban

U.S. imported record $1.2 billion worth of seafood from Russia last year, and amount is likely much higher if Chinese-processed Russian seafood is included

WASHINGTON—The breaded fish sticks on your dinner plate may be made with fish caught in Russian waters, despite a new import ban on Russian seafood.

The U.S. government in March banned imports of Russian fish and seafood products, along with other consumer items such as vodka and diamonds, as part of its expanding package of sanctions against Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. Still, many tons of Russian fish have been allowed to slip into the U.S. That is because, fishery industry experts say, complex supply chains that route through China often mask the Russian origin of the seafood—and the U.S. lacks the tools to trace the origin of these products.

“When you open a can of salmon, you don’t know if it’s Russian-caught or it is U.S. because we do not track that seafood,” said Sally Yozell, senior fellow and director of the Environmental Security program at the Stimson Center. “The American consumers do not support rebranded Russian seafood entering our markets. But unfortunately, they do not know because it is disguised as a Chinese product. “

For example, 27% of the fish caught by Russian vessels in Russian waters was estimated to have been shipped to China to be processed before being exported to the U.S., according to a 2021 report by the U.S. International Trade Commission. The fish products included pollock processed into filets or fish sticks or salmon canned at Chinese factories. These items are classified as imports from China, allowing them to bypass the current sanctions. Frozen crabs are often labeled as Alaskan crabs even if they are caught in Russia.

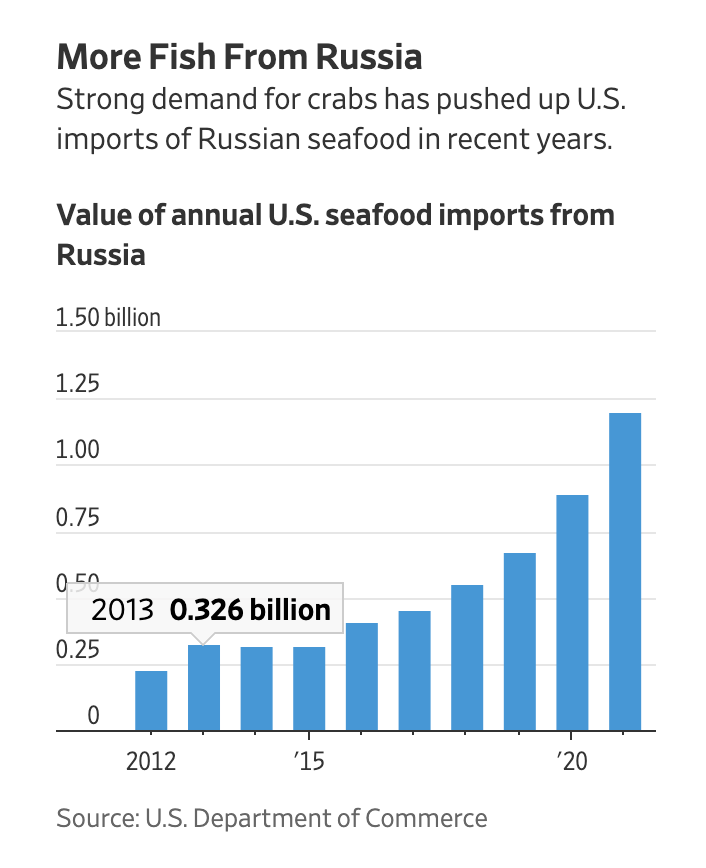

The fish stakes are huge for Russia as well as China. The U.S. imported $1.2 billion worth of seafood from Russia last year, a record amount and nearly triple the level in 2016, according to Commerce Department data, with crabs making up most of the overall imports. The amount is likely much higher if Chinese-processed Russian seafood is included, Ms. Yozell said.

The fish most likely to slip through the import ban is pollock, an inexpensive white fish used in breaded fish sticks, filet and fish-and-chips meals served in individual restaurants.

Americans consumed about 1 pound of pollock per person in 2019, making the unsung species the most popular fish after shrimp, salmon and canned tuna, according to the federal National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA. The main fishing grounds for pollock are the Bering Sea between Alaska and the Russian Far East, making Russia and the U.S. main providers of the fish.

The Association of Genuine Alaska Pollock Producers, a group representing Alaskan pollock harvesters and processors, estimates roughly 40% of pollock marketed to U.S. consumers are caught in Russian waters by Russian vessels. Nearly all of those fish are processed into filets and frozen in Chinese factories before entering the U.S., according to the association. That step in the supply chain provides them with made-in-China labels.

Chuck Hosmer, key principal of Romanzof Fishing Co. LLC, a Seattle-based fishing vessel operator, said American and Russian boats fish for crab and pollock in such proximity in the Bering Sea that they sometimes literally see each other. “We are very hopeful that this will reduce the amount of seafood we have to compete against domestically,” he said of the sanctions. “We get undercut by Russian products because their cost of doing business is much less.”

Environmental groups and some lawmakers say one way to make the import ban more effective is to expand the existing seafood-import monitoring system. It doesn’t cover fish such as pollock and salmon, making it difficult to trace and prove the items indeed originated from Russia.

To clamp down on importation of seafood caught through illegal and unregulated fishing, NOAA in 2016 launched the monitoring system. But it currently only covers 13 popular species such as shrimp, tuna and crab, and leaves 60% of imported fish outside of its scrutiny.

“If we really want to make sure that the crab or salmon on our dinner table isn’t supporting Putin’s violence or illegal fishing practices, we need to expand and improve our seafood traceability programs, and we need to do it now,” said Rep. Raúl M. Grijalva (D., Ariz.), chairman of the House Committee on Natural Resources.

At a hearing on the Russian seafood ban on Thursday, his committee will discuss expansion of the monitoring program, which has support of several Republican lawmakers.

Melaina Lewis, a spokeswoman for the National Fisheries Institute, a trade group of U.S. seafood businesses, said the effort to expand the monitoring system in the guise of Russian sanctions is “disingenuous.” The group supports a targeted response to hold Russia accountable but also points to the sanctions’ impact on seafood supplies and American seafood businesses. “We support a strong and smart response that is targeted and avoids unnecessary economic collateral damage on U.S. workers,” Ms. Lewis said.

By: Yuka Hayashi

Source: Wall Street Journal

Next Article Previous Article