The Environmental Battle Over the Mexican Border Wall

Legal challenges by environmentalists could delay construction, but key court rulings so far have favored the Trump administration

SONORAN DESERT, Ariz.—As President Trump pushes to speed construction of the Mexican border wall, both opponents of the wall and his administration are invoking the environment—one side to stop the barrier, and the other to build it.

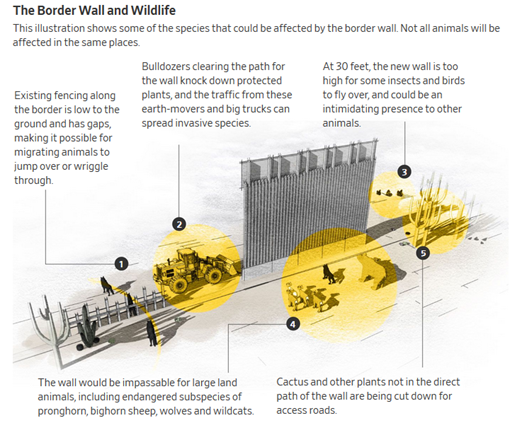

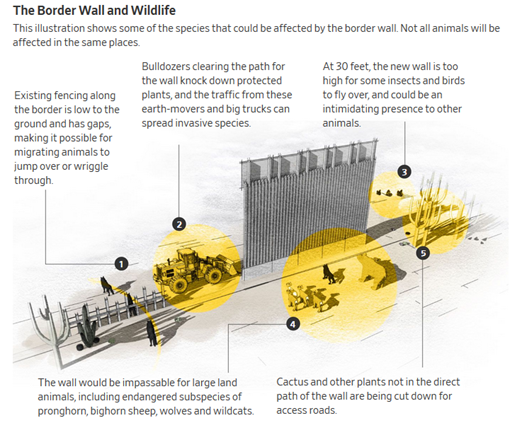

Environmental groups say an impassable 30-foot-high wall would prevent endangered pronghorn, wolves, wildcats and other animals from roaming the borderlands for food, water and mates, while also destroying native plants and other threatened species in parks and wildlife preserves that line the border like Arizona’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

Administration officials counter that migrants and smugglers trample brush that is habitat for endangered butterflies, owls and other species, and set signal fires that leave long-lasting damage to scrubland and trees.

“This is just a wild, no man’s land,” said William Perry Pendley, the Bureau of Land Management’s acting director, from the Otay Mountain Wilderness near San Diego. “We’re not managing this as a wilderness area because of forces out of our control.”

The Border Wall and Wildlife

The environmental debate will play out in court in the months ahead. The Center for Biological Diversity and three other groups petitioned the Supreme Court Jan. 31 to review lower court rulings that allowed the Trump administration to waive environmental rules to build the wall.

The Sierra Club, meanwhile, is co-plaintiff in a lawsuit challenging the use of emergency spending to build the wall, which has oral arguments scheduled for March 10 before the U.S. Court of Appeals in San Francisco. The Sierra Club claims legal standing on grounds that wall construction will destroy wilderness enjoyed by its members.

Key court judgments have so far favored the administration, which has invoked laws Congress passed dating back to the 1990s to give the president broad power to ignore the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act and other bedrock environmental laws. The Supreme Court issued a preliminary decision in July allowing the government to start construction.

Civil-rights groups, state and local governments, the Democratic-led House of Representatives and religious groups have all been part of legal challenges to the wall. But government attorneys and legal experts consider the environmental groups to be formidable challengers because of their legal standing and ability to bankroll an intense court fight.

If successful, the environmental challenges could block wall construction, or delay it for years. Legal experts, however, said the conservative majority on the Supreme Court makes environmentalists the underdogs in the fight.

For environmental groups, “there’s no question about the impacts on wildlife resources that they have an interest in protecting and their members have an interest in enjoying,” said Patrick Parenteau, an environmental law expert at Vermont Law School. “But it’s not going to overcome some of the legal problems that they have.”

Along the Border

Laiken Jordahl gazes into a ditch near wall construction at the Organ Pipe park in Arizona. It’s filled with bulldozed, rotting remnants of Arizona’s iconic saguaro cactus. These plants are protected species, except all those protections are waived for wall construction.

“It’s devastating,” he said. “Wherever else they build, it’s going to look like this.”

Mr. Jordahl, 28 years old, wrote threat assessments about the park for the federal government in his old job with the National Park Service. Now, an activist with the Center for Biological Diversity, he organizes protests and tracks wall construction, hiking around with cameras, a plastic jug of water and a fraying baseball cap for protection from the constant sun.

At Quitobaquito Springs, a green and reedy oasis, Mr. Jordahl crouches next to a clear spring, pointing to thumbnail-sized, endangered turtles floating by and to a particular species of endangered pupfish that lives in the U.S. only in this shallow stream.

The wall would tower over the oasis, double the height of the tallest nearby trees and cactus. The rust-colored steel of sections of the new wall already up in the park is a dark blot on a landscape otherwise bright with blue sky and dusty yellow desert. Last week, Mr. Jordahl turned his camera on to crews blasting rocks and earth out of a steep hillside to smooth a path for the wall.

The 30-foot height is insurmountable even for some species of birds and insects, scientists say. While it is technically a fence, with thick, diamond-shaped slats or bollards each a few inches apart, the barrier functions as a wall for a lot of the region’s wildlife.

In Organ Pipe, the wall replaces ranch-style fencing, a single iron crossbar and two strands of wire, the top one barbed, connecting posts no taller than roughly six feet. That fencing was a compromise that had been common in the region, blocking smugglers from driving in but allowing animals to hop over or wriggle through.

For Mr. Jordahl, the wall doesn’t make sense. Millions of dollars have been spent to revive animal populations in the area, the Sonoran pronghorn in particular from a population of only two dozen. It’s North America’s fastest land mammal, and a rare sight. It’s often called a “prairie ghost” because people who see it in the wild describe it as like seeing a ghost flicker across the desert, Mr. Jordahl said. The new wall would block them from finding mates and sustenance across the border.

The pronghorn is one of roughly 62 endangered species facing grave threats from the wall, with some at risk of extinction, according to a memo signed by 3,000 scientists in the journal BioScience in 2018. Projects like this shrink habitat and break apart ecosystems, making animals and plants more vulnerable to drought, disease and other threats, they said.

Desert Caravan

About 300 miles west of Organ Pipe, a caravan of SUVs and pickups rambled over a dirt access road that runs along the wall leading into the Otay Mountain Wilderness area southeast of San Diego. Mr. Pendley, the Bureau of Land Management’s acting director, was surveying the area as part of the process for the land to be approved for wall construction. BLM and other Interior Department agencies manage many of the federal lands where the wall is going up.

The caravan stopped at a scrub-covered mountain plateau, overlooking the sprawling suburbs of Tijuana. Mr. Trump said the wall is needed here to stop “an invasion” of undocumented immigrants. Mr. Pendley says that is why the wall is being built, but there are environmental benefits, too.

The ability to cross borders helps animals find food, water and mates. In January 2017 a tracking device showed a Mexican wolf entering the U.S. over or through a border fence designed to allow animals to pass. The Trump administration's new wall would replace that fencing with higher barriers and close other gaps that animals use.

There’s trash and footpaths through the brush. Fires burned 75 acres here in 2019, according to the Interior Department’s tally, and Mr. Pendley sees the remnants of pink flame retardant still lingering on some of the Otay Mountain’s plant life.

With 20 to 30 people coming through each day during last year’s peak, the traffic makes the area unsafe and an environmental hazard, federal agents said.

“The only way I can protect that is either put all my rangers on it 24/7, or put a wall there,” Mr. Pendley said in a later interview. “And so I support the president’s decision to construct a wall.”

Administration officials say they are taking steps to cushion the environmental impact. Workers have been transplanting some cactuses and other plants—110 in total as of September in Organ Pipe—if they are “in a healthy enough state to be relocated,” Border Patrol said in a statement. Interior Department and Border Patrol officials say they have been coordinating on plans to add some gates and gaps near waterways for animals to pass through, among other efforts to protect wildlife.

Construction is going forward with few of those plans being guaranteed or finalized.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection said that through Feb. 7 it has erected 119 miles of new barrier, mostly during the last 12 months, and almost all of it replacing old fencing. The administration has said it hopes to have 450 miles built or under construction by the end of 2020.

By:

Timothy Puko

Source:

Wall Street Journal

SONORAN DESERT, Ariz.—As President Trump pushes to speed construction of the Mexican border wall, both opponents of the wall and his administration are invoking the environment—one side to stop the barrier, and the other to build it.

Environmental groups say an impassable 30-foot-high wall would prevent endangered pronghorn, wolves, wildcats and other animals from roaming the borderlands for food, water and mates, while also destroying native plants and other threatened species in parks and wildlife preserves that line the border like Arizona’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

Administration officials counter that migrants and smugglers trample brush that is habitat for endangered butterflies, owls and other species, and set signal fires that leave long-lasting damage to scrubland and trees.

“This is just a wild, no man’s land,” said William Perry Pendley, the Bureau of Land Management’s acting director, from the Otay Mountain Wilderness near San Diego. “We’re not managing this as a wilderness area because of forces out of our control.”

The Border Wall and Wildlife

The environmental debate will play out in court in the months ahead. The Center for Biological Diversity and three other groups petitioned the Supreme Court Jan. 31 to review lower court rulings that allowed the Trump administration to waive environmental rules to build the wall.

The Sierra Club, meanwhile, is co-plaintiff in a lawsuit challenging the use of emergency spending to build the wall, which has oral arguments scheduled for March 10 before the U.S. Court of Appeals in San Francisco. The Sierra Club claims legal standing on grounds that wall construction will destroy wilderness enjoyed by its members.

Key court judgments have so far favored the administration, which has invoked laws Congress passed dating back to the 1990s to give the president broad power to ignore the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act and other bedrock environmental laws. The Supreme Court issued a preliminary decision in July allowing the government to start construction.

Civil-rights groups, state and local governments, the Democratic-led House of Representatives and religious groups have all been part of legal challenges to the wall. But government attorneys and legal experts consider the environmental groups to be formidable challengers because of their legal standing and ability to bankroll an intense court fight.

If successful, the environmental challenges could block wall construction, or delay it for years. Legal experts, however, said the conservative majority on the Supreme Court makes environmentalists the underdogs in the fight.

For environmental groups, “there’s no question about the impacts on wildlife resources that they have an interest in protecting and their members have an interest in enjoying,” said Patrick Parenteau, an environmental law expert at Vermont Law School. “But it’s not going to overcome some of the legal problems that they have.”

Along the Border

Laiken Jordahl gazes into a ditch near wall construction at the Organ Pipe park in Arizona. It’s filled with bulldozed, rotting remnants of Arizona’s iconic saguaro cactus. These plants are protected species, except all those protections are waived for wall construction.

“It’s devastating,” he said. “Wherever else they build, it’s going to look like this.”

Mr. Jordahl, 28 years old, wrote threat assessments about the park for the federal government in his old job with the National Park Service. Now, an activist with the Center for Biological Diversity, he organizes protests and tracks wall construction, hiking around with cameras, a plastic jug of water and a fraying baseball cap for protection from the constant sun.

At Quitobaquito Springs, a green and reedy oasis, Mr. Jordahl crouches next to a clear spring, pointing to thumbnail-sized, endangered turtles floating by and to a particular species of endangered pupfish that lives in the U.S. only in this shallow stream.

The wall would tower over the oasis, double the height of the tallest nearby trees and cactus. The rust-colored steel of sections of the new wall already up in the park is a dark blot on a landscape otherwise bright with blue sky and dusty yellow desert. Last week, Mr. Jordahl turned his camera on to crews blasting rocks and earth out of a steep hillside to smooth a path for the wall.

The 30-foot height is insurmountable even for some species of birds and insects, scientists say. While it is technically a fence, with thick, diamond-shaped slats or bollards each a few inches apart, the barrier functions as a wall for a lot of the region’s wildlife.

In Organ Pipe, the wall replaces ranch-style fencing, a single iron crossbar and two strands of wire, the top one barbed, connecting posts no taller than roughly six feet. That fencing was a compromise that had been common in the region, blocking smugglers from driving in but allowing animals to hop over or wriggle through.

For Mr. Jordahl, the wall doesn’t make sense. Millions of dollars have been spent to revive animal populations in the area, the Sonoran pronghorn in particular from a population of only two dozen. It’s North America’s fastest land mammal, and a rare sight. It’s often called a “prairie ghost” because people who see it in the wild describe it as like seeing a ghost flicker across the desert, Mr. Jordahl said. The new wall would block them from finding mates and sustenance across the border.

The pronghorn is one of roughly 62 endangered species facing grave threats from the wall, with some at risk of extinction, according to a memo signed by 3,000 scientists in the journal BioScience in 2018. Projects like this shrink habitat and break apart ecosystems, making animals and plants more vulnerable to drought, disease and other threats, they said.

Desert Caravan

About 300 miles west of Organ Pipe, a caravan of SUVs and pickups rambled over a dirt access road that runs along the wall leading into the Otay Mountain Wilderness area southeast of San Diego. Mr. Pendley, the Bureau of Land Management’s acting director, was surveying the area as part of the process for the land to be approved for wall construction. BLM and other Interior Department agencies manage many of the federal lands where the wall is going up.

The caravan stopped at a scrub-covered mountain plateau, overlooking the sprawling suburbs of Tijuana. Mr. Trump said the wall is needed here to stop “an invasion” of undocumented immigrants. Mr. Pendley says that is why the wall is being built, but there are environmental benefits, too.

The ability to cross borders helps animals find food, water and mates. In January 2017 a tracking device showed a Mexican wolf entering the U.S. over or through a border fence designed to allow animals to pass. The Trump administration's new wall would replace that fencing with higher barriers and close other gaps that animals use.

There’s trash and footpaths through the brush. Fires burned 75 acres here in 2019, according to the Interior Department’s tally, and Mr. Pendley sees the remnants of pink flame retardant still lingering on some of the Otay Mountain’s plant life.

With 20 to 30 people coming through each day during last year’s peak, the traffic makes the area unsafe and an environmental hazard, federal agents said.

“The only way I can protect that is either put all my rangers on it 24/7, or put a wall there,” Mr. Pendley said in a later interview. “And so I support the president’s decision to construct a wall.”

Administration officials say they are taking steps to cushion the environmental impact. Workers have been transplanting some cactuses and other plants—110 in total as of September in Organ Pipe—if they are “in a healthy enough state to be relocated,” Border Patrol said in a statement. Interior Department and Border Patrol officials say they have been coordinating on plans to add some gates and gaps near waterways for animals to pass through, among other efforts to protect wildlife.

Construction is going forward with few of those plans being guaranteed or finalized.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection said that through Feb. 7 it has erected 119 miles of new barrier, mostly during the last 12 months, and almost all of it replacing old fencing. The administration has said it hopes to have 450 miles built or under construction by the end of 2020.

Next Article Previous Article